Daniel Argimon’s work, of remarkable richness and variety, shows great unity and coherence in its different stages. The artist is considered one of the main representatives of Catalan Informalism, although his continuous desire to innovate with original materials and techniques, his constant experimentation with matter and fire, and the incorporation, through collage, of objects and elements found in his environment, led him to integrate into his work elements distinctive of American Pop Art and French New Realism. His production, highly personal, is characterized by the use of collage and fire, which, in short, gives meaning to most of his creations, whatever their period.

The consolidation of Argimon’s work took place in his informalist phase, which began in the late fifties and early sixties, when he started to work with great interest on pictorial matter, adding corporeal and dense elements to it, superimposing materials like talc, plaster, marble dust and latex. These paintings presented thick textures and dense clusters of matter in simplified and practically monochrome compositions. With them Argimon aimed, as he himself said, to “achieve a painting as grey as existence”, in keeping with the arid, sterile atmosphere of post-war Spain.

In the early 1960s, however, the painter began to incorporate by means of collage elements of reality into his works, an innovation that distanced him, to a certain extent, from the abstract informalist orthodoxy. Argimon integrated collages of crumpled and burnt papers and newspapers into his paintings, using them as another expressive material, as he did with latex, talcum powder or gypsum. On other occasions, he produced a series of works employing objects from his surroundings (doors, blinds, dies…), which he decontextualised and subjected to manipulation with paint stains and destructive processes through fire, another of the characteristic and constant elements in his work. The misery of the object, battered by the passage of time and deteriorated by use, reflected the artist’s vital anguish.

Soon, Argimon’s collages acquired a new direction and the elements incorporated in his works, strongly figurative, convey new significance to them. They had clear thematic references, mainly centred on socio-political problems and eroticism.

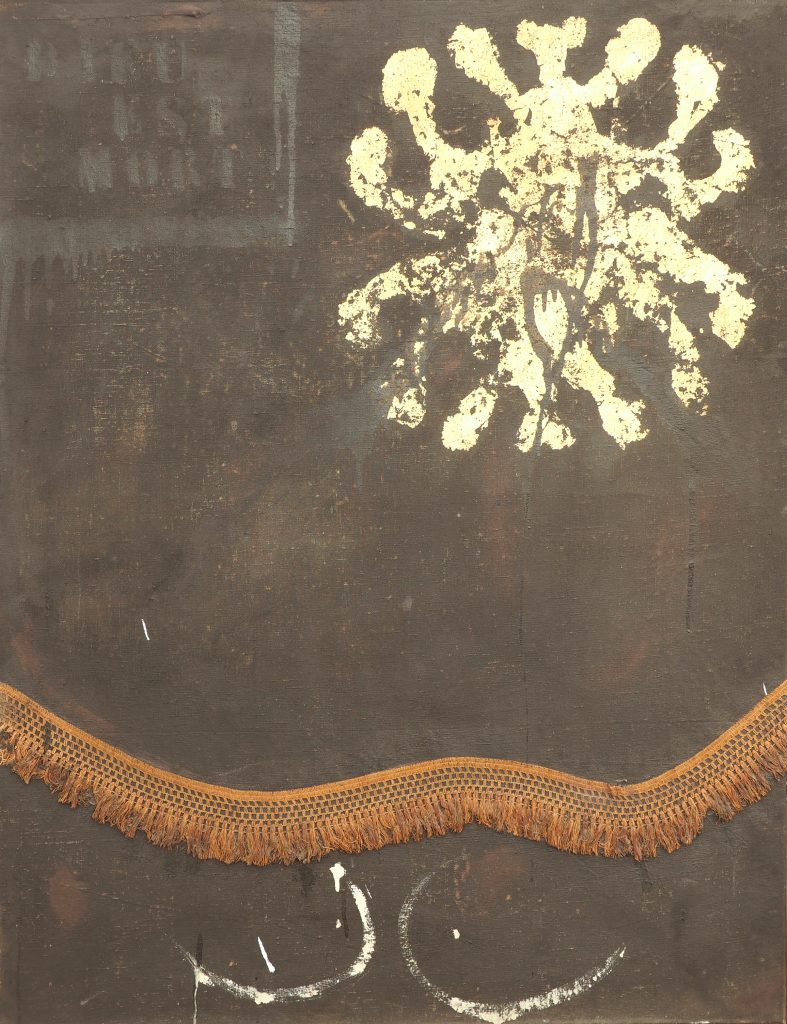

Thus, without abandoning the informalist aesthetic, between 1963 and 1967, Argimon added photographs, lace and other elements to his collages that recall the language of French New Realism and American Pop Art. The artist created highly personal type of work, in which images of people with radical political connotations, newspaper pages, photographs of models or even textile pieces, were integrated into completely informal surfaces. The paint was superimposed on the glued elements, with drips and stains distributed over the entire surface of the canvas.

This line of work, which he began to unfold through his collages, places him in the panorama of Spanish plastic art as an outstanding bridging figure between informalism and the languages linked to the new realisms. With Argimon, we find ourselves before an artist whose work is in constant oscillation between these new languages, integrated into his work through collage, and the informalist conception.

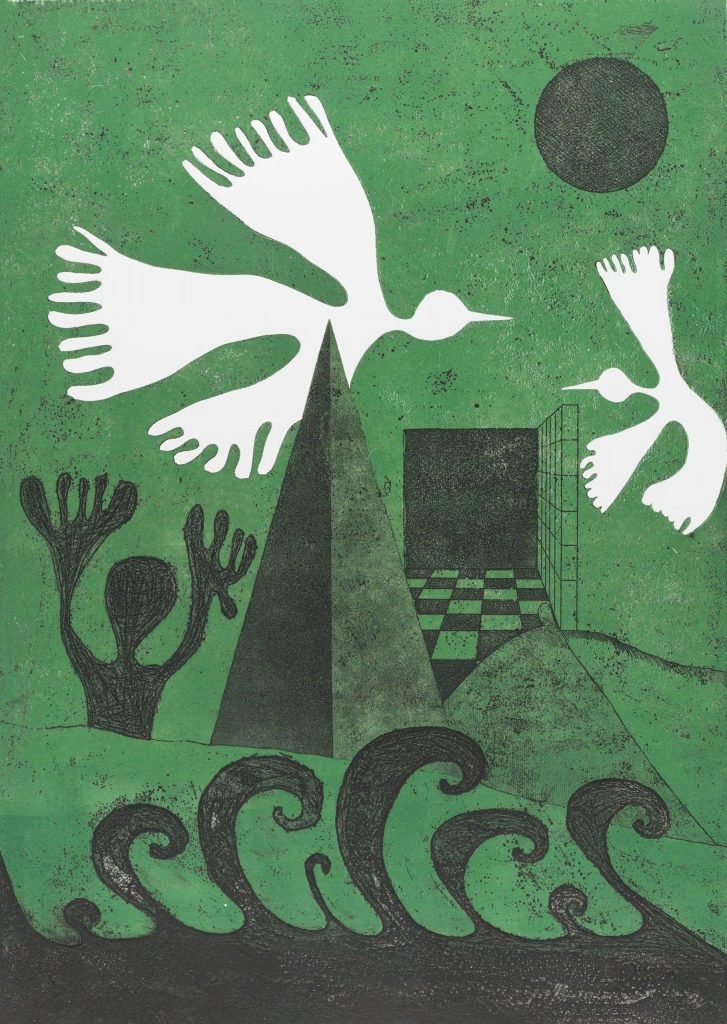

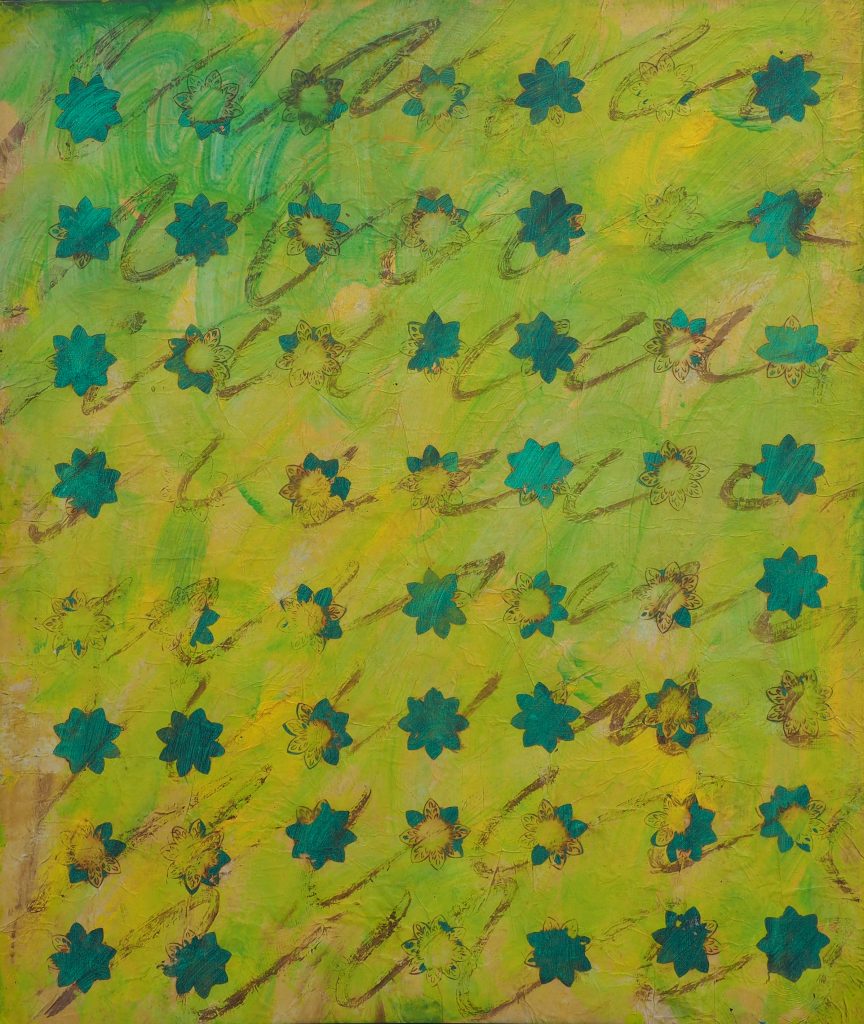

In 1969, on his return from the United States, the artist entered the most differentiated stage in his trajectory. Staying close to figuration through simplification and the abandonment of his work with matter, he aimed to convey a more direct message, continuing in his critical and committed struggle of social denunciation. During seven years, the influence of American Pop Art is evident in the use of colour and the plastic treatment of the themes. He focused on flat painting, using acrylics, opening up to colour with well-defined figures and silhouettes cut out in the background: enormous destructive boots, figures with their arms raised, threatening rifles, pigeons, elements of nature or sexual symbols that all make very explicit demands.

Within this language, Argimon produced his work of the largest dimensions: a mural in a building in Moratalaz, near Madrid, built by the architects Peter Hodkinson and Ricardo Bofill (1970).

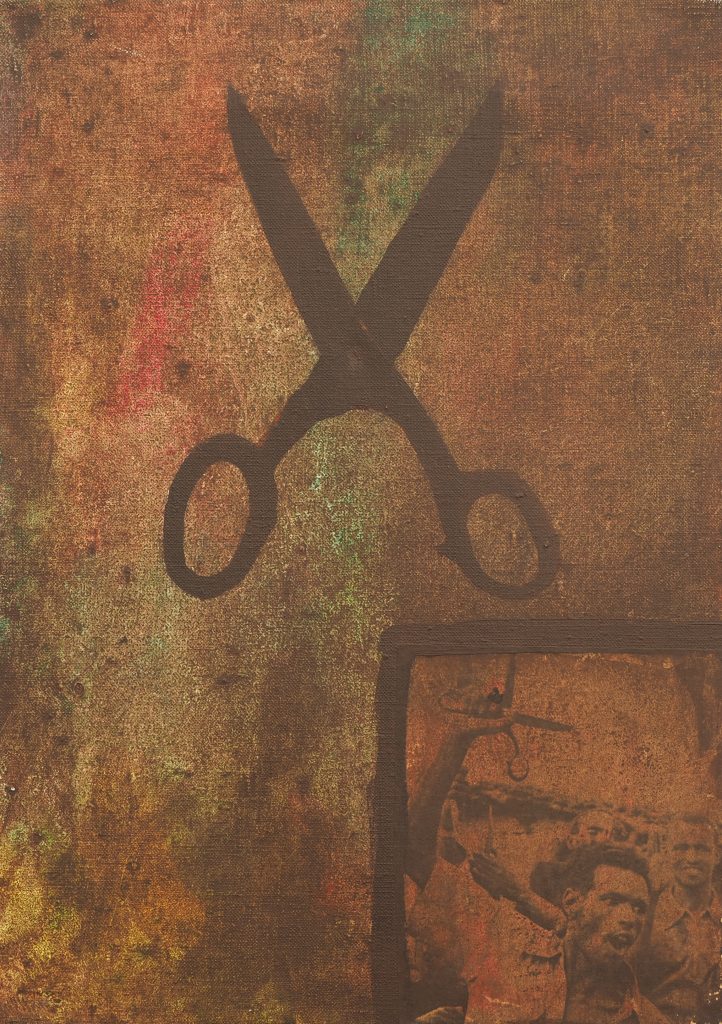

This period, of figurative influence, ended in 1977 with the series Eines (Tools), where the incorporation of reality came from the artist’s own work instruments. The tools painted in his works (hammers, saws, scissors, pliers…) took centre stage, but his approach was very different from what had been observed until then, mainly because the artist moved away from flat, bright colours, and textures, once again, played a primordial role, with the reappearance of informalist treatments of backgrounds. In this series, we find a total symbiosis and complementarity between the different languages of the time, so characteristic of Argimon’s work.

After this neo-figurative period, in 1978, the artist presented a collection of object-based works in line with the practices of New Realism, inaugurating a new stage in his career. Once more, he incorporated elements from the environment (plastic bottles, newspapers, matches, cardboard, brooms, bits of coal, pieces of cloth, wire, broken glass…) and like so, objects from everyday life and waste became the protagonists of his works. In them, he presented these elements of reality mostly transformed, metamorphosed again by fire, which he reuses and which, from this moment on, will be very present in his creations.

This short phase, lasting only one year, was a real tabula rasa for Argimon, insofar as it helped him to reflect on his own artistic evolution and to embark on a new stage in which he consolidated a language he had successfully developed in his informalist period, without abandoning experimentation and innovation.

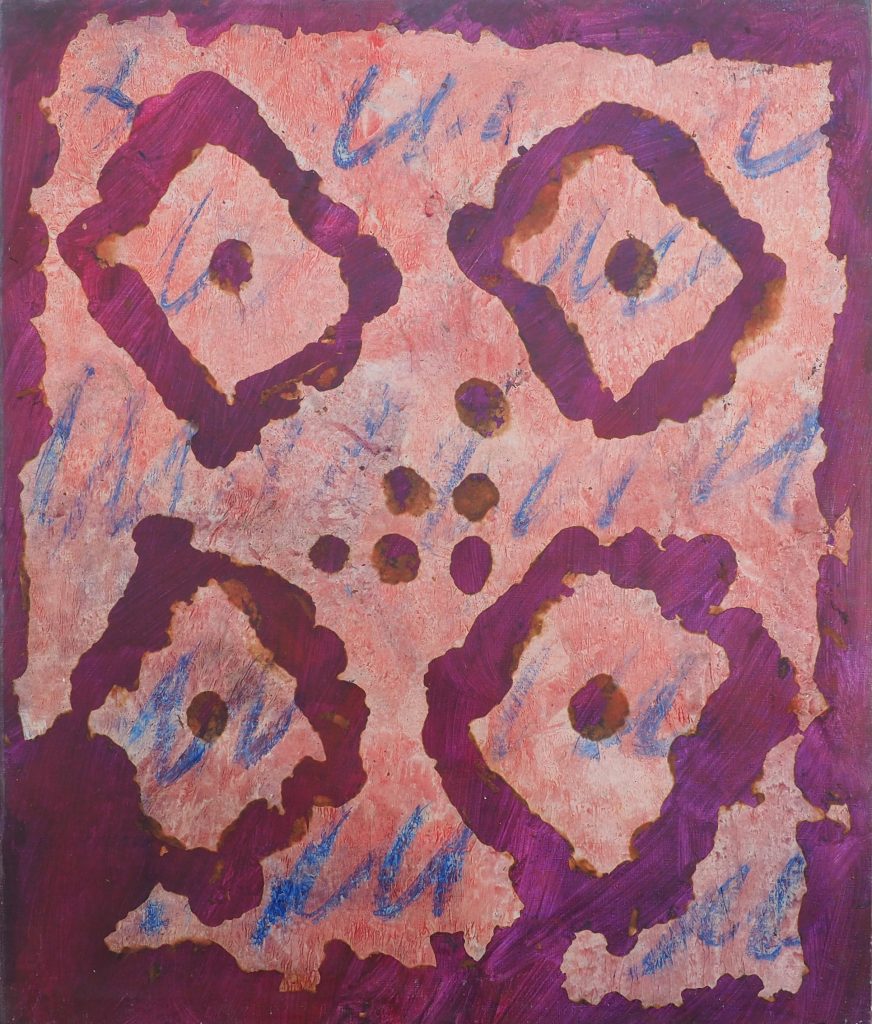

The painter then entered a phase in which he veered away from denouncing social issues, struggle and social outcry, and began a moment of inner withdrawal and introspection, deepening his relationship to the act of painting. Theme was no longer essential, nor was the reference to reality. The chromatic experience, the reencounter with the matter together with the qualities obtained by means of fire on paper became the central points of his work. It was in the eighties that the artist made the most systematic use of fire in his works, but not for its aggressive and destructive effect, characteristic of some earlier periods, but as a working tool, as an instrument for the creation and construction of his work, demonstrating a perfect mastery of the technique of burning paper. His compositions during the first half of the eighties were structured, devoid of rigidity, in geometric schemes and figures.

(130 x 100)

The work of this period was also characterised by an openness to colour: yellow ochres, bright reds, turquoise greens, and various shades of blue combine in a way that had never happened before. At the same time, the painter experienced a reencounter with matter and collage.

For almost three years, from 1985 to 1987, Argimon used papier-mâché to incorporate dense material areas to the background, with drips and splashes of paint.

The work of his last period, from the mid-1980s until his death, shows great maturity and fullness. In a certain way, it summarises and synthesises the different stages of his artistic career while reflecting on his creative and working process. Fundamentally, Argimon continued to show a special inclination for the collage of heterogeneous materials integrated in a material universe, a practice clearly linked to the beginnings of his creative work.

It is also necessary to mention Argimon’s interest in other artistic disciplines: cinema and printmaking in which he created works of remarkable quality. His dedication to the latter — particularly lithography and etching, with mostly very small runs —, has been a constant in his career ever since he produced his first lithograph in 1960. The complete and precise inventory of his graphic work is contained in the catalogues of the exhibitions held in the Franz Spiegel Buch gallery in Ulm (1988) and in the Museo Nacional de la Estampa in Mexico City (1991).

Since Argimon worked in a global way, the approaches and contributions he developed at each stage of his career are reflected in all the arts that he cultivated.